| Thomas J. Elpel's Web World Portal  Wildflowers & Weeds |

Wildflowers-and-Weeds.com

Wildflowers-and-Weeds.com Plant Identification, Foraging, and Ecology with Thomas J. Elpel Home | Plant Identification | Plant Families Gallery | Edible Plants | Mushrooms | Links Desertification & Weed Ecology | Weed Profiles | Search this Site |

Are you still thumbing through

|

See also: Plant Identification Resources Recommended by Tom |

Plants that are related to each other have similar characteristics for identification. Botanists have simply looked for patterns in plants and created groups called "families" according to those patterns. In the northern latitudes where there are hard freezes during winter, there are only about 100 broad patterns representing tens of thousands of plant species. Once you identify the family your wild flower belongs to then you can still use your color picture book to identify the species, but now you only have to look through a few pictures to find a match, not hundreds. Learn how right here:

Learning to Identify Plants by Families

It will forever change the way you look at plants

Grandma Josie always loved to walk her dogs down in the meadows, following cow trails through the thickets of willow and juniper along the creek. I loved to walk with her, and together we collected wild herbs for teas, such as yarrow, blue violets, peppermint, red clover and strawberry leaves. We drank herbal tea every day. When I was sick she gave me yarrow tea with honey in it, plus she buried cloves of garlic in cheese to help me get them down. Grandma kindled my love for plants. She taught me the plants she knew. Then I wanted to learn about all the rest.

We collected unfamiliar flowers on our walks, and paged through books of color pictures to identify them. It was not a fast process, but I was a kid and had the luxury of time. If I could not find the name of a specimen in our books, then I brought it into the herbarium at the university and asked for help. They keyed out the plant and gave me the Latin name for it. At home I researched the name through all of my books to learn anything I could about the uses for that species. In this way I learned most of significant plants of southwest Montana before I was out of high school, or so I thought.

We collected unfamiliar flowers on our walks, and paged through books of color pictures to identify them. It was not a fast process, but I was a kid and had the luxury of time. If I could not find the name of a specimen in our books, then I brought it into the herbarium at the university and asked for help. They keyed out the plant and gave me the Latin name for it. At home I researched the name through all of my books to learn anything I could about the uses for that species. In this way I learned most of significant plants of southwest Montana before I was out of high school, or so I thought.

Years later, I launched our school (now known as Green University® LLC and hosted an herbal class at our place. I thought I "knew" most of the plants discussed in the class, but Robyn, the herbalist, used an approach I had never seen before. We happened across several members of the Rose family, and Robyn pointed out the patterns-- that the flowers had five petals and typically numerous stamens, plus each of them contained tannic acid and were useful as astringents to help tighten up tissues. An astringent herb, she told us, would help close a wound, tighten up inflammations, dry up digestive secretions (an aid for diarrhea) and about twenty other things. In a few short words she outlined the identification and uses for the majority of plants in this one family.

Some of my books listed the family names of the plants, but never suggested how that information could be useful. I realized that while I knew many plants by name, I never actually stopped to look at any of them! This may sound alarming, but it is surprisingly easy to match a plant to a picture without studying it to count the flower parts or notice how they are positioned in relation to each other. In short, Robyn's class changed everything I ever knew about plants. From there I had to relearn all the plants in a whole new way. I set out to study the patterns among related species, learning to identify plants and their uses together as groups and families.

Some of my books listed the family names of the plants, but never suggested how that information could be useful. I realized that while I knew many plants by name, I never actually stopped to look at any of them! This may sound alarming, but it is surprisingly easy to match a plant to a picture without studying it to count the flower parts or notice how they are positioned in relation to each other. In short, Robyn's class changed everything I ever knew about plants. From there I had to relearn all the plants in a whole new way. I set out to study the patterns among related species, learning to identify plants and their uses together as groups and families.

My quest turned into a book Botany in a Day, to share with other people this "patterns method" of learning plants. On plant walks with a favorable selection of specimens to look at, I've been able to cover the critical patterns for identification and uses of seven or eight major families of plants, representing tens of thousands of species worldwide in just two hours.

I tell my students it is okay if they do not know the name of a single plant at the end of the walk, but I expect them to recognize family characteristics and be able to make logical guesses as to how those plants might be used. When we come to an unknown specimen in our walks, I don't tell the group what it is, they tell me, according to the patterns they have learned.

There are about 100 families of plants across the frost-belt of the continent, with at least 30 additional families occurring farther south where it never freezes. Through this article I will introduce you to seven of the largest and easiest-to-recognize families of plants, which are found worldwide. In the next hour or two you will learn the basic patterns of identification and many of the uses for more than 45,000 species of plants worldwide. Take a little bit of time to practice these patterns where ever you go-- in gardens or weed patches, botanical gardens, the nursery, the florist, or the wild. When you learn to instantly recognize these and other family patterns, the world of plants will never look quite the same again. The plant family descriptions below are meant to be read in order, as new ideas are introduced with each family to prepare you for the next one.

Mustard Family | Mint Family | Parsley Family | Pea Family | Lily Family | Mallow Family | Aster/Sunflower Family

Plants of the Mustard Family

Key Words: 4 petals and 6 stamens--4 tall and 2 short.

Mustard flowers are easy to recognize. If you have a radish or turnip blooming in the garden, then take a close look at the blossoms. When identifying flower parts, it is best to start on the outside of the flower and work towards the middle like this: sepals, petals, stamens, and pistil(s).

On the outside of the mustard flower you will see 4 sepals, usually green. There are also 4 petals, typically arranged like either the letters "X" or "H". Inside the flower you will see 6 stamens: 4 tall and 2 short. You can remember that the stamens are the male part of the flower because they always "stay men". The female part is the pistil, found at the very center of the flower.

For the purposes of the Mustard family, all you need to remember is "4 petals with 6 stamens--4 tall and 2 short". If you find that combination in a flower, then you know it is a member of the Mustard family. Worldwide there are 375 genera and 3200 species. About 55 genera are found in North America.

All species of Mustard are edible, although some taste better than others. In other words, it doesn't matter which species of mustard you find. As long as you have correctly identified it as a member of the Mustard family, then you can safely try it and see if you want it in your salad or not.

Most members of the Mustard family are weedy species with short life cycles like the radish. Look for them in disturbed soils such as a garden or construction site, where the ground is exposed to rapid drying by the sun and wind. The Mustards sprout quickly and grow fast, flowering and setting seed early in the season before all moisture is lost from the ground.

Most members of the Mustard family are weedy species with short life cycles like the radish. Look for them in disturbed soils such as a garden or construction site, where the ground is exposed to rapid drying by the sun and wind. The Mustards sprout quickly and grow fast, flowering and setting seed early in the season before all moisture is lost from the ground.

Also be sure to look closely at a Mustard seed pod, called a silicle or silique, meaning a pod where the outside walls fall away leaving the translucent interior partition intact. They come in many shapes and sizes, as you can see in the illustration, but they always form a raceme on the flower stalk, which looks something like a spiral staircase for the little people. With practice you can easily recognize the mustards by their seed stalks alone, and from fifty feet away. Identification by the seed stalks is helpful since many of the flowers are too small to peer inside and count the stamens without a good hand lens.

Interestingly, six of our common vegetables--cabbage, cauliflower, kohlrabi, Brussels sprouts, broccoli, and kale--were all bred from a single species of mustard, Brassica oleracea. Plant breeders developed the starch-storage abilities of different parts of the plant to come up with each unique vegetable. Commercial mustard is usually made from the seeds of the black mustard (B. nigra) mixed with vinegar.

As you become more familiar with this family, you will begin to notice patterns in the taste and smell of the plants. While each species has its own unique taste and smell, you will soon discover an underlying pattern of mustardness. You will be able to recognize likely members of the family simply by crushing the leaves and smelling them.

View flower photos from the Mustard Family.

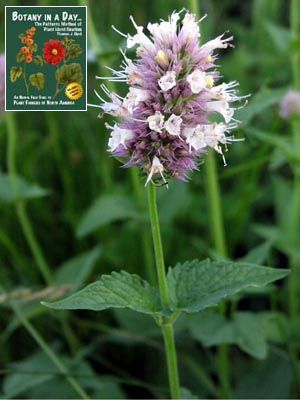

Plants of the Mint Family

Key Words: Square stalks and opposite leaves, often aromatic.

If you pick a plant with a distinctly square stalk and simple, opposite leaves, then it is very likely a member of the Mint family. Be sure to smell it too, since many species of the family are loaded with aromatic volatile oils.

The rich, spicy quality of these plants makes them useful in cooking, and nearly half the spices in your kitchen come from this one family, including basil, rosemary, lavender, marjoram, germander, thyme, savory, horehound, plus culinary sage (but not sagebrush!), and of course mint, peppermint, and spearmint.

For the beginning botanist, that is all you really need to remember: "square stalks with opposite leaves, and usually aromatic". Worldwide there are about 180 genera in the Mint Family representing some 3500 species. Approximately 50 genera are found in North America.

For the beginning botanist, that is all you really need to remember: "square stalks with opposite leaves, and usually aromatic". Worldwide there are about 180 genera in the Mint Family representing some 3500 species. Approximately 50 genera are found in North America.

Medicinally this family is rich in volatile oils, especially menthol, often used as the penetrating vapors in cough drops. These spicy oils are stimulating and warming, causing the body to open up and sweat; so most of these plants are listed as diaphoretic in herbal books. This property can help you break a fever. A fever is the body's way of "cooking" the microorganisms that cause infections. Using a diaphoretic herb can help raise a mild fever just high enough to "cook" a virus, thus "breaking" or ending the fever.

Volatile oils are also highly lethal to microorganisms. On camping trips I often use aromatic Mints to help purify questionable water. Eating a few Mint leaves after drinking from a creek certainly won't kill everything in the water, but it sure helps.

You can safely sample any member of the Mint family. Some species like the Coleus, a house plant with red and green leaves, have no aroma at all, while a patch of the more potent Agastache may bring tears to your eyes just passing through.

Note that there are a handful of other plants with square stems and opposite leaves, which may be confused with the Mints. Those plants are found in the Loosestrife, Verbena, and Stinging Nettle families, but none of them smell minty.

As you become proficient at identifying members of the Mint family by their square stalks, opposite leaves, and spicy aroma, you should also familiarize yourself with the flowers.

Notice in the illustration that there are 5 sepals, all fused together so that only the tips are separate. The 5 petals are also fused together, but note how asymmetrical or "irregular" the flowers are, compared to the more symmetrical or "regular" Mustard flowers. Some Mint flowers are much more irregular than others, but if you study them closely you will see that they typically have 2 petal lobes up and 3 petal lobes down. Inside the flower there are 4 stamens, with one pair longer than the other. As you learn these patterns of the Mint family you will be able to recognize and use them anywhere in the world.

View flower photos from the Mint Family.

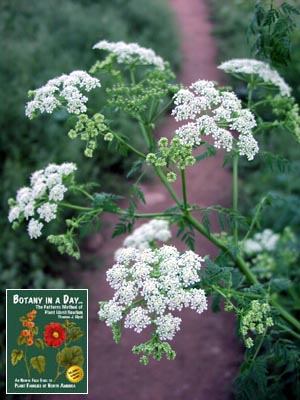

Plants of the Parsley or Carrot Family

Key Words: Compound umbels. Usually hollow flower stalks.

The Parsley Family includes some wonderful edible plants like the carrot and parsnip, plus more aromatic spices found in your spice cabinet, such as anise, celery, chervil, coriander, caraway, cumin, dill, fennel and of course, parsley. But unlike the Mustard or Mint families, the Parsleys are not all safe for picking and eating. In fact, the Parsley family is among the most important families of plants to learn, since it includes the deadliest plants in North America: poison hemlock and water hemlock. Note that the hemlock tree is totally unrelated.

For identification, the most distinctive pattern of the Parsley family is the "compound umbels". Notice how all the stems of the flower cluster radiate from a single point at the end of the stalk, kind of like an umbrella. At the end of each of these flower stems there is another umbrella of even smaller stems, hence the "compound umbrella" or "compound umbel". To be a true umbel, the stems or spokes must all radiate from exactly the same point. Other flowers like the common yarrow may appear to have compound umbels, but look closer and you will see that the flower stems are staggered off the main stalk, so the yarrow is not a member of this family. Another pattern of the Parsley family is that the stems are usually, but not always hollow. Kids have been poisoned using hemlock stems for straws.

For identification, the most distinctive pattern of the Parsley family is the "compound umbels". Notice how all the stems of the flower cluster radiate from a single point at the end of the stalk, kind of like an umbrella. At the end of each of these flower stems there is another umbrella of even smaller stems, hence the "compound umbrella" or "compound umbel". To be a true umbel, the stems or spokes must all radiate from exactly the same point. Other flowers like the common yarrow may appear to have compound umbels, but look closer and you will see that the flower stems are staggered off the main stalk, so the yarrow is not a member of this family. Another pattern of the Parsley family is that the stems are usually, but not always hollow. Kids have been poisoned using hemlock stems for straws.

When you recognize the compound umbels of the Parsley family then you know you have to be careful. You must be 100% certain of what these plants are before you harvest them for food or medicine. More than that, you must be right! People die just about every year thinking they have discovered some kind of wild carrot.

So how do you distinguish the poisonous members of the family? Don't rush it. You might think that learning plants is just a matter of filling up the disk space in your head with data, but there is a bit more to it than that. No matter what you study, whether it is plant identification, art, or math, you learn by connecting neurons in the brain to build a neural network for processing the information. Getting started is the most dangerous time, because all the plants tend to look alike-- kind of green mostly. Just practice pointing out compound umbels everywhere you go, starting with the dill or fennel in the garden. The more you practice this and other family patterns, the more you will learn to see just how unique and different each plant is.

When you are proficient at recognizing the major plant families, then go back and start studying more of the individual plants. Even then, avoid rushing to conclusions. Keep in mind that when your goal is to find an answer, then you will find one, whether it is right or not.

If you are positive that you have identified a member of the Parsley family correctly, that's good. Now wait and see if you are still sure of your answer in a few days or a week. When you get good at recognizing certain species every time you see them, then you might consider trying out their appropriate edible or medicinal uses. Worldwide there are about 300 genera in the Parsley family, representing more than 3000 species. About 75 genera are native to North America.

View flower photos from the Parsley Family.

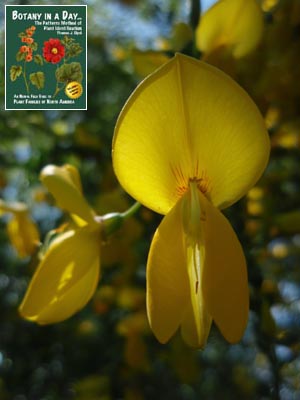

Plants of the Pea Family

Key Words: "Banner, wings, and keel". Pea-like pods, often with pinnate leaves.

If you have seen a pea or bean blossom in the garden, then you will be able to recognize members of the Pea family. These are irregular flowers, with 5 petals forming a distinctive "banner, wings, and keel", as shown in the illustration. The banner is a single petal with two lobes though it looks like two that are fused together. Two more petals form the wings. The remaining two petals make up the keel and are usually fused together. The proportions of the parts may vary from one species to another, but as long as there is clearly a banner, wings and keel, then the plant is a member of the Pea family. Pea-like pods are another distinctive trait of the family.

For practice, look at a head of clover in the lawn. You will see that each head is a cluster of many small Pea flowers, each with its own banner, wings, and keel. As the flowers mature each one forms a tiny pea-like pod. I'll bet you never noticed that before!

For practice, look at a head of clover in the lawn. You will see that each head is a cluster of many small Pea flowers, each with its own banner, wings, and keel. As the flowers mature each one forms a tiny pea-like pod. I'll bet you never noticed that before!

The Pea family is very large, with 600 genera and 13,000 species worldwide, all descendants of the very first Pea flower of many millions of years ago. Over time the Peas have adapted to fit many different niches, from lowly clovers on the ground to stately trees that today shade city sidewalks. Families this large often have subgroupings called subfamilies and tribes. It works like this:

The most closely related species are lumped together into a single group or "genus". For example, there are about 300 species of clover in the world. Each one is clearly unique, but each one is also a clover, so they are all lumped together as one genus, Trifolium (meaning 3-parted leaves) and given separate species names such as T. arvense or T. pratense, etc.

If you compare clovers to other members of the Pea family then you will see that they share more in common with alfalfa and sweet clover than with other plants like beans or caragana bushes. Therefore the clover-like plants are lumped together as the Clover tribe while the bean-like plants are lumped together as the Bean tribe, and so forth, for a total of eight tribes. Each of these tribes share the distinctive banner, wings and keel, so they are all lumped together as the Pea subfamily of the Pea family. All Peas across the northern latitudes belong to this group.

As you move south you will encounter more species of the Pea subfamily, plus other plants from the Mimosa and Bird-of-Paradise-Tree or Senna Subfamilies. These groups include mostly trees and shrubs, but also a few herbs. Their flowers do not have the banner, wings, and keel, however most have pinnate leaves, much like the one in the illustration, plus the distinctive pea-like pods that open along two seams. Each subfamily is distinct enough to arguably qualify as a family in its own right, but they still share enough pattern of similarity between them to lump them together as subcategories of a single family.

Overall, the plants of the Pea family range from being barely edible to barely poisonous. Some species do contain toxic alkaloids, especially in the seed coats. Many people are familiar with the story of Christopher McCandless who trekked into the Alaska wilderness in 1992 and was found dead four months later. He had been eating the roots of Hedysarum alpinum, and assumed the seeds were edible too, so he gathered and ate a large quantity of them over a two-week period. The seeds, however, contained the same toxic alkaloid found in locoweed, which inhibits an enzyme necessary for metabolism in mammals. It is now believed that McCandless was still eating, but starved to death because his body was unable to utilize the food. Even the common garden pea can lead to depression and nervous disorders with excess consumption. So it is possible to poison yourself with members of this family, but it takes some effort.

Pea Family / Pea Subfamily

Try to identify the banner, wings and keel in each of the pictures.

Broom Tribe | Golden Pea Tribe | Licorice Tribe | Clover Tribe | Trefoil Tribe

Mimosa Subfamily | Caesalpinia (Bird-of-Paradise Tree) Subfamily

Plants of the Lily Family

Key Words: Flowers with parts in threes. Sepals and petals usually identical.

If you find a plant with parallel veins in the leaves and regular flowers with parts in multiples of three, chances are you have a member of the Lily family. The flowers have 3 sepals and 3 petals, usually identical in size and color. Any normal person would just say there are 6 petals, but botanists distinguish a difference. Starting from the outside of the flower you count towards the inside: sepals, petals, stamens and pistil. In Lilies, the first layer consists of 3 colored sepals, while the second layer consists of 3 colored petals. Such botanizing may seem overly academic, but it becomes important as you learn more complex family patterns.

Members of the Lily family have 6 stamens, although some may be lacking anthers. The tip of the pistil, called the "stigma" is also noticeably 3-parted. You are most likely to confuse the Lily family with the Iris family, except that the Irises have only 3 stamens, and Iris leaves grow from the base in a flat plane, as if the plants have been squashed in a book. Worldwide there are about 250 genera and 3,700 species in the Lily family including 75 genera in North America.

Members of the Lily family have 6 stamens, although some may be lacking anthers. The tip of the pistil, called the "stigma" is also noticeably 3-parted. You are most likely to confuse the Lily family with the Iris family, except that the Irises have only 3 stamens, and Iris leaves grow from the base in a flat plane, as if the plants have been squashed in a book. Worldwide there are about 250 genera and 3,700 species in the Lily family including 75 genera in North America.

As you study plants and their relationships you will realize more and more that evolution isn't just an abstraction that happened in the past, but an active process that you can reach out and touch. For example, if one population of day lilies is similar but different from another population, then we have to decide if the differences constitute mere variations within a species, or a whole new species. This is kind of like trying to find the line between two neighboring cities. There might be a lot of difference downtown, but you could drive through the suburbs from one to the other without seeing the boundary. How do you know when you have crossed the line from one species into a new one?

The same is true at the family level. Among the Lilies there is enough variation to justify breaking the family apart into smaller families of more closely related plants. For instance, daffodils are so different from the more typical lilies described here that they really deserve a family of their own. The trouble is that daffodils are closely related to plants that are closely related to other plants that are closely related to more typical Lilies. So where do you draw the line between one family and the other? In the effort to clearly distinguish these groups, botanists have proposed to break the Lily family up into as many as 70 distinct families, but to no avail. Recent genetic studies are helping to clear up the confusion, and will eventually require a complete rewrite of the family. In the interim, I rely on the historical subfamilies that work adequately to group the Lilies into their approximate relationships.

Virtually everything in the Lily subfamily is edible, such as onions and blue camas, however, there are a few deadly plants in the Bunchflower subfamily (with bunches of little white or greenish flowers), like the death camas which could easily be mistaken for edible Lilies. For this reason, it is important to harvest lilies for food only when you can positively identify them, usually when in bloom.

The Asparagus subfamily includes lilies that produce berries instead of dry seed capsules. Some of the berries are barely edible, while others are not. The Agave subfamily includes those spiny plants of the desert southwest, the agave, sotol and yucca, any of which can be used as a source of fiber for making cordage or rope. The Aloe subfamily includes the mucilaginous Aloe vera so favored for treating sunburns. The daffodil belongs to the Amaryllis subfamily.

View flower photos from the Lily Family.

Plants of the Mallow Family

Key Words: 5 separate petals and a column of stamens. Mucilaginous texture.

If you have seen a hollyhock or hibiscus flower, then you can recognize the Mallow family. Wild species may be smaller, but you will know you have a Mallow when you find a funnel-shaped flower with 5 separate petals and a distinctive column of stamens surrounding the pistil. There are also 3-5 partially united sepals, often surrounded by several bracts. Crush any part of the plant and rub it between your fingers. You will notice a mucilaginous (slimy) texture, even in seemingly dry, desert species.

Worldwide there are about 85 genera and 1500 species, including 27 genera in North America. Hollyhock, hibiscus, and cotton are members of this family. Cotton is the only member of this family with documented poisonous properties. All others seem to be safe for edible and medicinal uses. Okra is the edible fruit of a variety of hibiscus. Marshmallow was originally derived from a type of hollyhock. Some other members of the family can be used as marshmallow substitutes. The ground up root or seeds are covered with water and boiled until half the liquid is gone. Then the liquid is beaten to a froth and sugar is added. It should make something resembling whipped cream.

Worldwide there are about 85 genera and 1500 species, including 27 genera in North America. Hollyhock, hibiscus, and cotton are members of this family. Cotton is the only member of this family with documented poisonous properties. All others seem to be safe for edible and medicinal uses. Okra is the edible fruit of a variety of hibiscus. Marshmallow was originally derived from a type of hollyhock. Some other members of the family can be used as marshmallow substitutes. The ground up root or seeds are covered with water and boiled until half the liquid is gone. Then the liquid is beaten to a froth and sugar is added. It should make something resembling whipped cream.

The plants contain natural gums called mucilage, pectin, and asparagin, which gives them a slimy texture when crushed. It is the presence of these gums that creates the marshmallow effect. The members of the Mallow family are mostly edible as a salad greens and potherbs, although not very commonly used, probably due to their slimy consistency. The flowers and seeds are also edible.

Medicinally, the mucilaginous quality of the Mallows may be used just like the unrelated Aloe vera or cactus: externally as an emollient for soothing sunburns and other inflamed skin conditions, or internally as a demulcent and expectorant for soothing sore throats.

View flower photos from the Mallow Family.

Plants of the Aster Family

Key Words: Composite Flowers in disk-like heads.

The uniqueness of the Aster or Sunflower family is that what first seems to be a single large flower is actually a composite of many smaller flowers. Look closely at a sunflower in bloom, and you can see that there are hundreds of little flowers growing on a disk, each producing just one seed. Each "disk flower" has 5 tiny petals fused together, plus 5 stamens fused around a pistil with antennae-like stigmas. Look closely at the big "petals" that ring the outside of the flower head, and you will see that each petal is also a flower, called a "ray flower," with it's petals fused together and hanging to one side. Plants of the Aster family will have either disk flowers, ray flowers, or both. When the seeds are ripe and fall away, you are left with a pitted disk that looks strikingly like a little garden plot where all the tiny flowers were planted.

The flower head is typically wrapped in green sepal-like "bracts" (modified leaves) surrounding the disk. The true sepals (found around individual flowers) have been reduced to small scales, or often transformed into a hairy "pappus", or sometimes eliminated altogether.

The flower head is typically wrapped in green sepal-like "bracts" (modified leaves) surrounding the disk. The true sepals (found around individual flowers) have been reduced to small scales, or often transformed into a hairy "pappus", or sometimes eliminated altogether.

One of the best clues for identifying members of this family is to look for the presence of multiple layers of bracts beneath the flowers. In an artichoke, for instance, those are the scale-like pieces we pull off and eat. Most members of this family do not have quite that many bracts, but there are frequently two or more rows. This is not a foolproof test, only a common pattern of the Aster family. Next, look inside the flower head for the presence of the little disk and ray flowers. Even the common yarrow, with its tiny flower heads, usually has a dozen or more nearly microscopic flowers inside each head, and the inside of a sagebrush flower head is even smaller. Keep in mind that many members of this family have no obvious outer ring of petals, including sagebrush.

The Asters are the largest family of flowering plants in the northern latitudes, with 920 genera and 19,000 species found worldwide, including 346 genera and 2,687 species in the U.S. and Canada. Only the Orchid family is larger, but it is mostly restricted to the tropics.

Many flowers from the Aster family are cultivated as ornamentals, including Marigold, Chrysanthemum, Calendula, and Zinnia. Surprisingly few are cultivated as food plants other than lettuce, artichoke, endive, plus the seeds and oil of the sunflower.

The Aster family includes many subfamilies, only a few of which are native to North America. The Chicory/Dandelion subfamily and Aster subfamily have long been recognized by taxonomists. The Thistle and Mutisia subfamilies were formerly classified as tribes within the Aster subfamily, but recently reclassified and promoted as subfamilies themselves.

North American Subfamilies of the Aster Family

Click on the links below to see photos and learn more about each subfamily of the Aster family.

Chicory / Dandelion Subfamily | Thistle / Artichoke Subfamily | Aster Subfamily

Check out Botany in a Day

Return to the Plant Families Index

Return to the Wildflowers & Weeds Home Page

Dear Mr. Elpel,

"Botany in a Day is hands down the best plant book I have ever come across. I wish I had this book years ago. Thanks for all the time and effort you put into it. You have made plant identification so much

easier, compared to a lot of my other books."

Bryon Steiner

Steiner Fine Art

Sacramento, California

|

Looking for life-changing resources? Check out these books by Thomas J. Elpel:

|

|

|