Exported Species

Eurasian native plants exported to North America

Any plants common to Eurasia and North America prior to western colonization are considered circumpolar species, as covered in page one of this article. Since colonization, however, many additional species have become circumpolar, being introduced from Europe and Asia to North America, or vice versa, from North America to Eurasia. Given enough time, any of these species may have found a means to jump continents on their own. Thanks to human transportation, however, numerous species have been introduced in both directions all at once.

Most new species blend in with native ecology and enhance biodiversity. For example, broadleaf plantain has become widespread across North America, yet isn't invasive. Native Americans sometimes called it "white man's footsteps," because it appeared wherever settlers traveled, often growing directly in rutted trails.

Most new species blend in with native ecology and enhance biodiversity. For example, broadleaf plantain has become widespread across North America, yet isn't invasive. Native Americans sometimes called it "white man's footsteps," because it appeared wherever settlers traveled, often growing directly in rutted trails.

Unfortunately, a few species become invasive, such as spotted knapweed (Centaurea maculosa), becoming dominant over millions of acres, often to the exclusion of native plants. These species are not problematic within their native homeland, where they have co-evolved with other plants, fungi, and insects for millions of years. Yet, when unleashed in a new continent, they explode across the landscape, often using survival strategies that natives are unprepared to defend against.

For example, spotted knapweed kills neighboring plants by draining them of nutrition through a symbiotic relationship with soil fungi. Grasses and herbs that evolved with knapweed in Eurasia were able to adapt and survive, while North American natives did not have the opportunity to develop the defensive mechanisms.

The problem is greatly exacerbated by changes in the grazing sequence due to colonization. North American rangelands were historically grazed by bison and shepherded by wolves. Bison roamed the land in dense herds, bunched together for protection against the ever-present wolves. Bison ate as they moved, trampling seeds, organic matter, and manure fertilizer into the soil along the way. Rather than revisiting their own excrement, bison continually moved to fresh grasslands, ensuring ample recovery without overgrazing.

Unfortunately, exterminating wolves and erecting fences caused a change in the grazing sequence that made North American rangelands infinitely more vulnerable to invasive species. Ecologically, cows are not much different than bison, except in their management. Instead of moving in tight bunches and rototilling seeds and organic matter into the soil, cows disperse widely across a field and stay in the same pastures way too long, eating tender green grasses again and again. Rangelands become overgrazed, and more critically, over-rested. Without herd impact to trample seeds and organic matter into the soil, new grasses struggle to germinate, resulting in progressive desertification as bare ground spreads between the plants. This barren ground is ideally suited to invasives such as knapweed, which explode across the landscape, draining nutrition away from the remaining natives. Millions of acres of beautiful rangelands have been converted to desertified wastelands of scratchy knapweed.

While I didn't encounter any spotted knapweed in Sweden, I did find several other knapweed species growing as if they belonged there, which they do. In addition, I recognized several other species native to Europe, but introduced and sometimes problematic in North America.

While I didn't encounter any spotted knapweed in Sweden, I did find several other knapweed species growing as if they belonged there, which they do. In addition, I recognized several other species native to Europe, but introduced and sometimes problematic in North America.

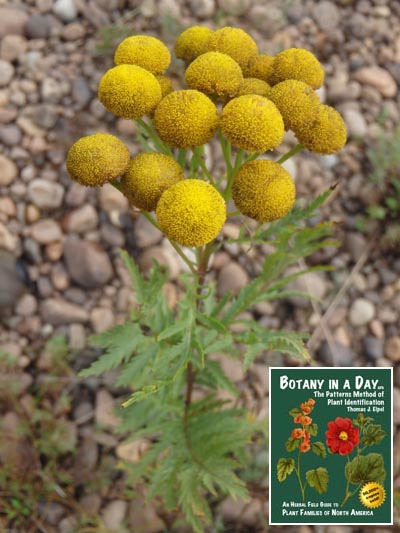

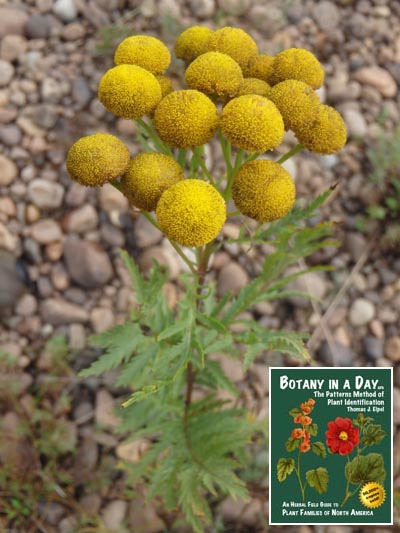

For example, common tansy (Tanacetum vulgare) is native to Eurasia, yet somewhat invasive in North America, often forming dense patches along the banks of irrigation ditches and stony streams across the American West, especially streams disturbed by mining activity. Unlike knapweed, tansy is a slow-moving invasive, forming dense, stable patches to the exclusion of other plants. Being highly aromatic and bitter, neither cows nor horses will eat it. However, sheep and goats seem to relish the plants. I battled tansy on my own property in Montana, initially through grazing and later with herbicides, to completely eradicate the plant along an abandoned irrigation ditch.

It is therefore a strange experience to encounter this same plant in Sweden, where it belongs, without feeling a degree of animosity towards it! Tansy grew in scattered clumps along the Klarälven River, rooted in the moist, gravelly riverbank where there was little competition and seemingly ample opportunity for the plant to explode and become dominant, yet it didn't. In fact, the plants often seemed anemic, as if they were struggling to survive at all. I did appreciate the dry, dead stalks as kindling for fire-starting where dry fuel can be scarce.

Scroll down for a look at some species native to Sweden and Eurasia that have become widespread in North America since colonization.

Botanizing Sweden

1. Intro and Circumpolar Species | 2. Exported Species | 3. Introduced Species

4. Cultivated Flowers | 5. Native Flowers | 6. Native Shrubs and Trees

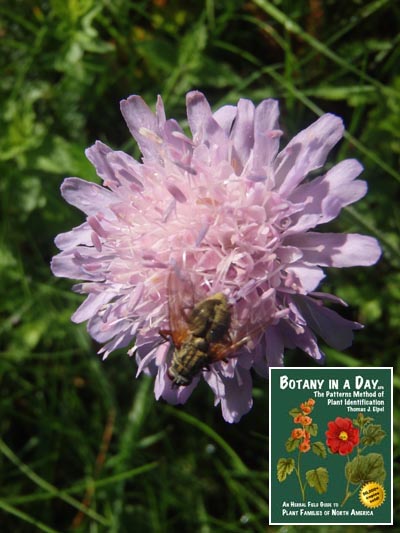

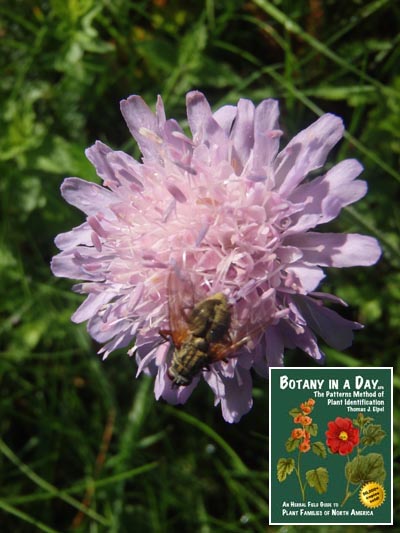

Field scabious: Knautia arvensis. Blue buttons was traditionally placed in the Teasel Family, which is now considered a subfamily of the Honeysuckle Family. |

Blue Buttons: Knautia arvensis. |

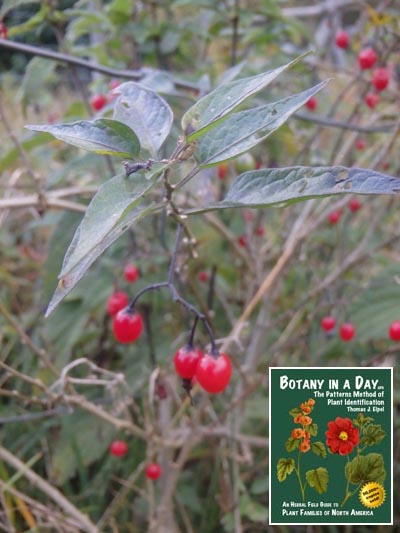

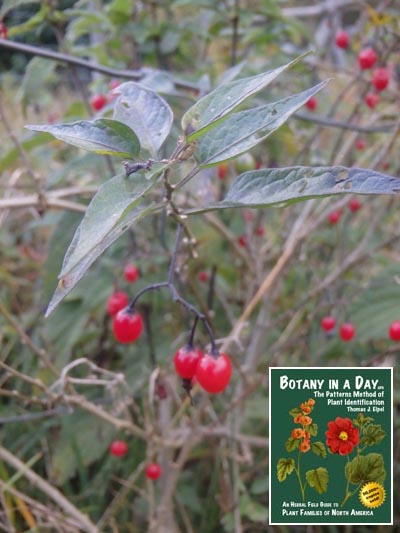

Bittersweet Nightshade: Solanum dulcamara. Nightshade belongs to the Nightshade Family. |

|

Botanizing Sweden

1. Intro and Circumpolar Species | 2. Exported Species | 3. Introduced Species

4. Cultivated Flowers | 5. Native Flowers | 6. Native Shrubs and Trees

Check out Botany in a Day

Return to the Wildflowers & Weeds Home Page

Wildflowers-and-Weeds.com

Wildflowers-and-Weeds.com

While I didn't encounter any spotted knapweed in Sweden, I did find several other knapweed species growing as if they belonged there, which they do. In addition, I recognized several other species native to Europe, but introduced and sometimes problematic in North America.

While I didn't encounter any spotted knapweed in Sweden, I did find several other knapweed species growing as if they belonged there, which they do. In addition, I recognized several other species native to Europe, but introduced and sometimes problematic in North America.